At Furman we are really lucky to have well-equipped classrooms that make it very easy to display a computer screen, project a score, and play music from a device with audio output. Partly as a result of this, and after reading a bunch of excellent blog posts by Kris Shaffer about incorporating technology into music theory classes, I’ve found myself making greater use of online resources in my classes.

Last year, I used many of the great ideas in Brian Alegant’s “Listen Up!: Thoughts on iPods, Sonata Form, and Analysis without Score,” (Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 21) when I taught form to sophomores. Alegant’s basic point—and this has become even more true since the article was published—is that great recordings are at our fingertips, and it’s easier than it’s ever been to use them in and out of the classroom. When I taught the Form and Analysis part of that class, I often used the online recording databases that Furman subscribes to. Lots of universities have subscriptions to the Naxos Library or the EMI Classical Music library. (Furman also subscribes to DRAM, a particularly nice archive of American music recorded on the New World Records and CRI labels.) These are all great resources, but I realized fairly quickly that they aren’t great for in-class use. Their search functions are not particularly intuitive, and, because they are browser-based, they can be unreliable. Even when I’d create a playlist before class, I could never be sure that a recording was really going to play when I pressed the play button! For all of these reasons, my students are even less likely to use them outside of class.

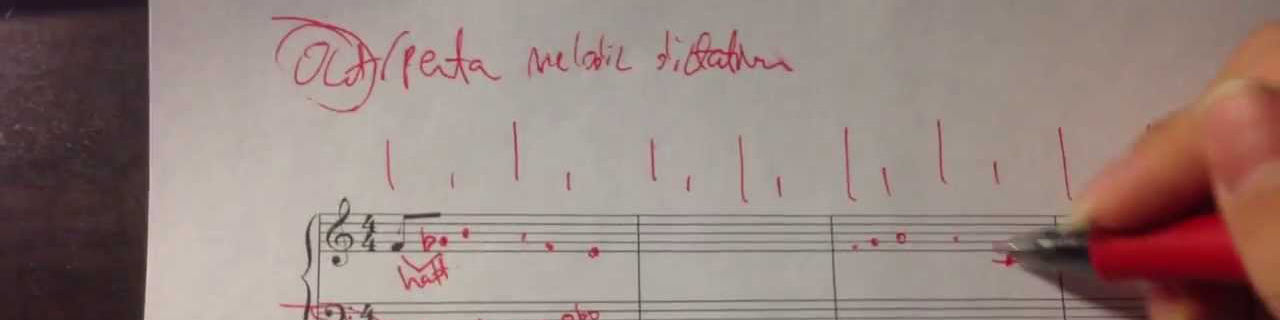

But the ability to incorporate good-quality recorded music into my classes has become too important to me to give up because of these shortcomings. Furman’s theory curriculum is structured around Steve Laitz’s “The Complete Musician,” and the most recent edition, which separates workbooks into “written” and “musicianship” skills, has made it even easier to use Laitz as a stand-alone aural skills text. On the musicianship side, Laitz’s text really emphasizes holistic listening skills: bass-line dictation, form identification, and so on. And students develop these skills through listening to a variety of instrumental and vocal ensembles playing “real music.”These are tough skills to master, and unlike harmonic idioms, melodic dictation—more traditional listening skills—I can’t emulate a string quartet in class!

Laitz’s musicianship workbook is fairly-well stocked with examples—more than I can get to in class—but students always want more practice, and it’s nice to have lots of extra examples if you want to emphasize something in particular. For example, I’ve been teaching modulation mostly in relation to the opening phrase of Minuets. Laitz has a few examples, but I want my students to have lots of exposure to these types of piece. They’ll be composing one for an end-of-term project, and in addition to being great pieces for studying modulation, they are great pieces for studying phrase structure and for becoming acquainted within certain Classical schemata. We’ve been talking about “Montes, Fontes, and Pontes,” in particular.

Spotify is a relatively new, but really wonderful resource for recordings of all kinds of music. And it’s great for in-class use because it is easy to search, and it isn’t browser-based. Most importantly, I can count on music playing when I click play. I’ve been using Spotify along with the Remoteless app for iPhone so that I can play music while walking around the class and watching/helping my students. It’s an even better tool outside of class. I’ve been creating Spotify playlists stocked with listening examples that are relevant to whatever we are working on in class. ~~For example, here’s my playlist for modulation and binary form.~~ I send my students that playlist, along with a DropBox link to a folder containing a list of the listening excerpts from the playlist and screenshots of the answers taken from IMSLP. Students pick something to listen to, note the key, and try dictate the bass line, identify what type of phrase they hear, and so on. Most importantly, this is all really easy for me to maintain. If I hear something promising on Spotify, I can easily drag it to the appropriate playlist, drop a screenshot of the passage from IMSLP into the DropBox, and type its title, key, and the location of the passage (for example, 0:00-0:17) into the DropBox text file.

My hopes are that all of this makes my students more likely to spend time listening outside of class. Listening skills are difficult to improve for lots of reasons. Because class time is limited, I want to remove any practical barriers that limit my students’s ability to practice on their own.